The Man Who Wouldn’t Hide

He was born Garson David Goldstein in Rochester, NY on October 25, 1914. My dad never liked the name Garson as a kid, so he called himself David. Dave for short. And that’s how everyone knew him – as David Goldstein.

He was born Garson David Goldstein in Rochester, NY on October 25, 1914. My dad never liked the name Garson as a kid, so he called himself David. Dave for short. And that’s how everyone knew him – as David Goldstein.

But my father didn’t change his last name. I never asked him why, but maybe it was because he was too proud of being Jewish to hide who he was, despite growing up during a time when anti-Semitism was a way of life in much of America as Ken Burns reveals in the new PBS special “The U.S. and the Holocaust.” Space was very limited for him in colleges and universities, and Eastman Kodak and Bausch + Lomb refused to hire him even after he graduated.

My father just kept looking forward to the future and worked as hard as he could to succeed.

My father walked to elementary school in the 1920s, and after the Great Depression began in 1929, he got up before dawn and slugged through the icy snow delivering newspapers to help his mother whom he affectionately called “Ma.” His mother was a Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrant from Poland with a babushka on her head, and his father was a cabinet maker from the Ukraine who was often out of work during the Depression.

In his diary, my father writes how he hated selling newspapers, but he sold so many that he was chosen to meet President and Mrs. Hoover at the White House on Christmas Day, 1930 with the First Annual Patriotic Pilgrimage of the Newspaper Boys of America. (There he is, wearing a tie and hiding his buck teeth behind a half-smile, in the second row, seven boys over from the President’s left shoulder.)

In 1932, my father applied to the University of Rochester and was accepted, despite what he later claimed was a 5% Jewish quota at the time.

My father showed no excitement in his diary though. The reason was, he couldn’t afford to go. Instead, he went to work. He lived with his Aunt Minnie in Brooklyn and worked as a hospital orderly, wheeling patients around for a year. With that money, he was able to study at the U of R for two years. Then he returned to Brooklyn for another year to earn enough money to finish school. He graduated from the U of R Institute of Optics in 1939 ten years after the school opened, the first optics education program in the nation.

But, “there were restrictions…” as the late historian Arthur Hertzberg says in the Ken Burns special. “Jews could barely get jobs in engineering.”

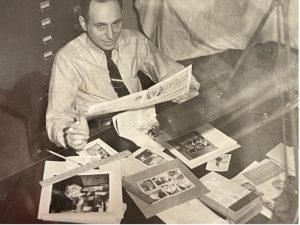

My father shrugged his shoulders, worked for a Jewish optical firm during the Second World War, and started his own company in 1946 – Elgeet Optical – with a boyhood friend named Mort London who did manage to get hired by Kodak because no one knew he was Jewish!

Elgeet designed and manufactured movie camera lenses, U.S. missile tracking devices, and microscopes. Its Navitar wide-angle lens was even used on the Tiros 1, the world’s first television infraRed observation and weather satellite now hanging in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. The launch of that satellite and its first black-and-white pictures of Earth were front-page news on April 1, 1960.

My father started a few more companies before passing on his last – Navitar – to my two youngest brothers and leaving us all behind in 1996. Despite all his achievements, some of my father’s happiest moments were simply sitting at the head of a long dining room table with his wife Jeanette and his eight children at our Passover seders each year. He struggled to read the Hebrew in the Passover Haggadah, but he refused to make it easy on himself and read the English translation. Hebrew was part of his heritage, like Yiddish.

My father was very proud of who he was, and what he achieved during his 81 years despite the discrimination he faced makes me very proud of him.

He could have easily changed his last name along with his first, but he never did. As the engraving on his gravestone says, “His Memory Remains An Inspiration For His Wife and Children Whose Lives Have Been Shaped By His Legacy of Greatness.”